Tracheal stenosis information

The trachea is the airway tube connecting the voice box to the lungs. It is made up of 16-20, C-shaped rings of cartilage. Cartilage is firm and not hard as bone and is similar to what makes the ears and nose.

Sometimes these C- rings are complete or O-shaped that does not allow normal tracheal growth. This causes congenital tracheal stenosis. The stenosis could be short segment (few rings affected) or long segment (when several rings are involved). The stenosis may be in the neck or in thorax or sometimes in both.

Causes

Congenital tracheal stenosis is a birth defect and the cause is unknown. It could form during the embryological development of the trachea.

Acquired stenosis occurs due to intubation trauma, neck injury and tracheostomy itself.

Signs and symptoms

Typically, a neonate will have noisy breathing, also called stridor. There are pent up secretions in the trachea and this gives the breathing a washing machine like character. In severe cases, the child could stop breathing and turn blue. There could be associated cardiopulmonary anomalies for which the infant undergoes a surgery. The condition is diagnosed either during intubation, or extubation or when the child presents with repeated chest infections that are out of proportion than routine lung infections.

It is more the severity of narrowing than the length of stenosis that decides the symptoms.

Diagnosis

It is the symptoms, signs and more importantly a suspicion of such a condition that points to its diagnosis. The diagnosis is confirmed during transnasal flexible laryngoscopy and tracheobronchoscopy, which allows the doctors to look inside the trachea using a telescope (a thin, flexible / rigid optique with bright light and camera) which shows a magnified image of the entire airway.

Clearly, one needs to have very thin optics to go past the stenosis and see the airway beyond the narrowing. The endoscopy needs to be done very carefully without inducing any trauma, which itself can swell up the trachea.

The child will have a CT scan of the thorax, an ECHO (echocardiogram or ultrasound scan of the heart) to check related anomalies concerning the heart and large thoracic vessels.

Surgical treatment

There is no role for dilatation or use of stents for the stenotic segment. A congenital airway stenosis should never be dilated. The small elastic cartilage rings will expand with dilatation, but within a short time, they will return back to their original size with added dangerous swelling.

The treatment depends on the number of tracheal rings affected.

A short segment stenosis is best treated by a resection and anastomosis (removing the narrowed portion and re connecting the normal wider portions).

A tracheostomy-induced stenosis is treated by tracheal resection and anastomosis.

In select cases of cervical (neck) trachea stenosis, we have removed upto 6-8 tracheal rings in children and upto 4-5 rings in adults with successfully end to end anastomosis. The amount of diseased trachea that can be removed has to be seen as per each individual case, but certainly is more difficult in adults due to increasing calcification in the cartilage.

If a child has a long segment tracheal stenosis, an operation called ‘slide tracheoplasty’ may be needed. Such a long segment starts in the neck and extends into the thorax.

Some patients may have an existing tracheobronchomalacia (softening of the trachea and bronchi) and need non invasive ventilation by a mask (CPAP) after the surgery.

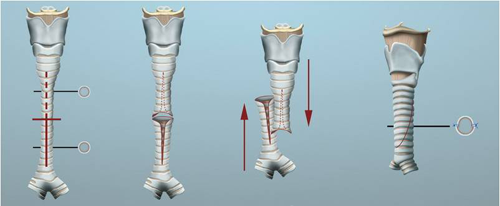

Principle of slide tracheoplasty

The principle is to add on (slide) 2 narrow tubes on top of each other to give a single well healed mucosalised tube with a large lumen. The length of the entire stenotic segment shortens by half, but the internal diameter increases 4-fold. This change in the tracheal dimensions does not affect its normal growth.

Steps of surgery

The operation is done in collaboration with a cardiac surgeon and lasts for about 4-5 hours.

To allow continuation of the surgery, the surgeon will use a heart-lung bypss system. The surgery begins with an incision (cut) in the child’s neck and an extension to the chest, which allows an adequate access to the problem.

The trachea and the stenotic segment are identified and the stenotic segment is divided into two parts - upper and lower -. The upper part is cut at the back and the lower part in front. The 2 parts are then slid over, so that the lower and the upper parts are on top of the other. The 2 segments are then stitched together. In the end, the trachea is only slightly shorter than the orginal form, but stronger and wider.

Events before the surgery

On your arrival in Lausanne, you will be hospitalized under the responsibility of either Service of Otorhinolaryngology (for an adult) or the Department of Pediatrics and Service of Otorhinolaryngology (in case of a child). You will then meet the doctors, who will give you more information regarding the management protocol. The endoscopy, surgery and other exams, if needed, will be discussed. They will answer all the questions you may have. Naturally, questions arising after the intervention will be discussed with you on day by day basis. You will be giving a consent form that needs to be signed authorizing the doctors to conduct the endoscopy and various interventions.

Another group of doctors will explain about the anaesthesia. All reports of the child from the referring doctor will be checked and if needed, other set of exams (blood, heart, X-rays) will be conducted.

Operation risks

We will conduct the operation in collaboration with a team of cardiac surgeons. It is a major surgery and involves correction of associated heart and large vessel malformations during the same time as that of the tracheal stenosis. The two teams will discuss with the parents the risks related to their individual specialities and entirely with respect to the child.

The hospital has all the necessary expertise and the material to manage all complications that may arise during the interventions. There could be bleeding either during or after the intervention for which, the child may need to go back to the operating theatre for a surgical exploration and stop this bleeding. After the surgery, the child will have suction drains inserted in the thorax, which drain away hematomas and secretions that are common after the surgery. These drains will be removed within a couple of days.

There could be a risk of infection for which the child is given antibiotics.

Sometimes the trachea remains narrow after the operation. In such a case, the narrowed reconstruction can be widened (dilated) and calibrated using a balloon during another separate procedure under general anaesthesia.

In some children, associated collapsible, soft and floppy airway (tracheomalacia) needs treatment. If it is too floppy, the child needs to be given forced oxygen by a mask (CPAP -continuous positive airway pressure).

We have plenty of experience, an excellent infrastructure and back up facilities in treating these very complex conditions.

Post operative period

The child is transferred to the Intensive Care Unit to recover. During the initial period after surgery, the child will have a tube passed through the nose into the airway and connected to a ventilator. There will be a feeding tube passed into the nose, a urinary catheter and a central vein catheter. The child will be given antibiotics for a few days.

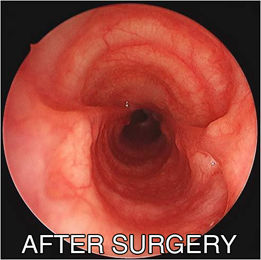

The first few days after surgery are critical. He will be given chest physiotherapy to keep the lungs in good condition. A week after the operation, the child will have a check endoscopy, to see how the trachea is healing. If it is healing well, the child will be extubated and given non invasive ventilation by a mask. This will continue until the doctors feel that the child can breathe by himself. In cases of severe pre existing tracheobronchomalacia, the mask ventilation is continued until the airway becomes stable and is non collapsible.

Further endoscopies are planned at 1 and 3 months after the surgery. It is possible that sometimes, the operated site may be dilated so as to optimally calibrate the airway.

After discharge from the hospital

The child returns home after complete healing of the trachea (3-4 weeks), and the family is comfortable managing him at home. The parents are encouraged to be in touch with us by email and call us in following circumstances:

- If there is a reappearance of noisy, stressful breathing.

- The child is not feeding well.

Some children need to have further treatment for the floppy (malacic) trachea. Non invasive ventilation (CPAP) will have to be given to the child at home. The parents would have received this training at our hospital and will need to monitor the oxygen saturation at night during this period.

For patients staying outside Switzerland, a systematic plan of follow up is prepared taking into consideration the long distance of travel and individual country insurance policies.